For a long time, I’ve been telling myself that “everyone is living life for the first time.”

To me, the thought justifies my uncertainty, deepens my understanding of others, and reminds me that I should not fear the future or the decisions I must make for myself, by myself.

Remembering that the majority of the world’s population is well under 50 years of age–and still living for the first time despite their accumulated experiences–awakens my own confidence and feelings of abundance. It helps me recognize the potential that is left unused by nearly every person that has ever lived. It is a recollection that shows me that I should have no fear of judgement or fear of pursuing something that is not seen as acceptable or a societal norm. Like, literally, no one knows what they’re doing. They may pretend to have their life under control, or they may think they know the key to existence, but really, they’re just going through life in a way that has been dictated to them since childhood. But, they, like you and me, can unlearn their childhood conditioning and pursue LITERALLY ANYTHING because no one has the right to tell them not to. It’s their first and only life, and they must live it the way they want.

And the same goes for you. So, please, for the sake of everything fleeting and beautiful, read this blog post, and then do something wonderfully unconventional for yourself.

Why fear judgement? It is pointless and holding you back.

Even if people had a valid reason for judging your actions, choices, behaviors–which they never will, by the way–they can never truly judge you in relation to your experiences, upbringing, current situation, etc., so you must not let their opinions bother you. A lot easier said than done, I know, trust me. But there is also the fact that they are likely dissatisfied with their own lives and will die never having pursued anything that truly brought them feelings of joy or freedom. So really, you can’t feel bad for yourself and any negative things being said about you. You can only feel bad for the unhappy human who comforts themself by speaking poorly of another person.

Okay, another scenario. Maybe no one is even noticing what you are doing in your little corner of the world. While this is probable, you likely feel self-conscious and begin to convince yourself that your every move is being watched anyways. Completely untrue; people have their own things going on and do not spend their every moment analyzing you. However, if this were the case, why should that bother you? All it means is that you are brave enough to do something different than the masses. They watch you because they are intrigued and maybe even jealous of your open individuality.

If you are doing something that has never been done before–or something that comes with a negative stigma–it is helpful to think of yourself as a pioneer in whatever domain you are pursuing. There have been pioneers in every major religion, for example, and now those religions have millions of followers. But to get that point of popularity, there had to be some people who were mocked, outcasted, and even martyred before the others could see, accept, and then openly welcome these new ideas. Fortunately for us, most of society has advanced in such a way that we won’t be sacrificing our lives when we chase unconventionality.

No one really knows what they’re doing.

In case you haven’t noticed, every single person around you is pretending they know what they are doing. They try to make it seem like they have figured out how to fulfill their life’s purpose and that they have no doubts whatsoever about the process of getting there. But, really, they have not the faintest clue what’s going on… And that’s okay.

Everyone has uncertainties, even on a day-to-day basis. Should I quit my job? Am I with the right person? Is this how I want to spend the rest of my youth? The rest of my life? You get the gist. The future spans in so many directions, but the average person plays it safe and follows in the footsteps of their parents. If not that, they watch their peers and get in line. No choices are their own. It’s sad, really, that no one knows how to think for themselves any more. These days,“free-thinkers” refers to a minority, and that just isn’t right.

And, when we do have inspirations and epiphanies and messages from the divine, it’s embarrassing how few of us act on them. We waste so much time doubting ourselves and not taking advantage of our health and capabilities that we end up doing nothing at all. In instances like these, we need to remember that there is no right way of doing anything. We must tell ourselves to get up, stop rotting, and take action. Explore our passions, show our unconventionalities, and make progress towards something substantial that is not rooted in tradition.

What even are societal norms and why do people follow them?

There are too many ways to answer this question, but, ultimately, the average human is a coward. And I don’t mean this as an insult. Simply put, we all have a fight-or-flight instinct. And, naturally, most of us choose to flee from the unfamiliar. In moments of stress, fighting seems to be the less safe option and no risk ever worth it.

So, if all we ever do is run back to our comfort zones, of course little progress is made in the way of discovering new territories. We revert back to the ways of our ancestors. Or more commonly, the approval of our family and friends. Yes, the people closest to us may be the ones keeping us stagnant. It’s nothing they do or say, exactly. Rather, it is what we are afraid of them doing or saying if we choose to pursue something outside of the realm of ordinary and acceptable. However, once we recognize this truth, it becomes easier to fight this mindset and break free of the voices holding us back. You are not here to be understood but to understand yourself.

Don’t forget to watch the clouds and talk to the trees.

So, this is the part where you have all these grand ideas in your head. You visualize yourself emerging from the safety of an underground bunker and into the light of every glorious thing you have ever wanted. Good for you. Now, you must chase these things, show yourself as a new person, and break free of every convention you have ever believed or hid behind. It will be hard, at first, but once you truly understand that there is not a single human who is better than you and there is not a single person in your life who has the right to judge you, you will be free.

We have endless possibilities to break the rules, challenge stigma, and enter into our highest states of being. But, with this, we must never forget where we’ve come from. While there is no one who will ever be better than, you will also never be better than them. They may be further behind you in figuring out they have the freedom to decide their own lives without outside influences, but they are human too. Ground yourself in cloud watching and tree talking. All of us are made up of the same soil we stand on. For that very reason, we must develop understanding for others but also live our brief lives on our own terms.

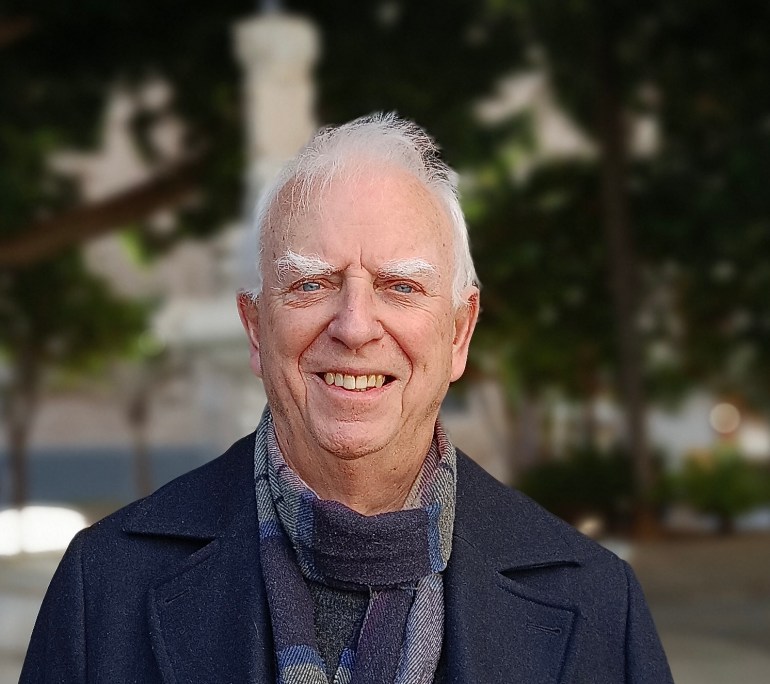

Jordan Eve Morral